Health center and quilombola school: the struggle changes life

Here’s a Wikipedia article explaining what “quilombola” stands for Transquilombo: this is how the bumpy road that connects all quilombos to the south bank of the Maicá River is called by close ones. By it, leaving the Bom Jardim quilombo you can reach Tiningu in just a few minutes. And it is in Tiningu that Bena is found, or rather: Raimundo Benedito da Silva Mota, historical character of the region – I have been following the leaders since I was 15 years old, today I am 60: 45 years of struggle. Today, Bena is president of the Quilombo Tiningu Remnants Association and vice president of FOQS (Federation of Quilombola Organizations in Santarém, in English). 45 years: Bena has seen the world come and go and come back and remain where it is, so he speaks calmly. And he recommends calm too – This is an area for who managed to escape from the “senzalas” [slave quarters]; you have to be patient with the historical moment. The Tiningu community has existed since 1844 – it is 176 years old – and it was only in October 2018 that Incra (National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform, in English) published the community recognition and demarcation decree in the Official Gazette. The white bureaucracy was late by almost two centuries – and there is still one last step for the final title: the signature of the President of the Republic. He, Jair Bolsonaro, the same who said – I went to a quilombo once. The lightest African descendant there weighed a hundred kilos. They do nothing. I don’t think he was usefull even as a breeder; and also – As far as I’m concerned, everyone will have a gun at home, there won’t be an inch demarcated for indigenous reservation or quilombola. Obviously these racist speeches echo in the racist structures of the Brazilian State: for example, the allocation of public resources for the titling of quilombola territories has fallen by more than 97% in the last five years. This is part of the story “What really happens in the Amazon Forest”. Browse content: INTRODUCTIONPart 1 (central page): What really happens in the Amazon ForestPart 2: Who is favored by Bolsonaro’s responses to the fires?Part 3: The “win-win” of companies with the financialization of naturePart 4: But after all, who is behind these crimes? STORIES1) The siege explained on a map2) A port stuck in the “mouth” of the river3) Before the port arrives (if it does), the impacts already did4) [you are here] Health center and quilombola school: the struggle changes life5) Curuaúna: on one side, soy. And on the other? Also soy Even so, Bena doesn’t lose his temper: what are four years, or a handful more, in the face of centuries of resistance – Uncle Babá who told me all stories, he was 108 years old, and Bena still keeps the oral tradition alive and tells and retells the stories of Tiningu, from the days when his neighbors and family members had to leave the region because the children suffered from anemia and there was no health center nearby; so it was necessary to row for almost two hours until reaching Santarém, but the adults also lacked strength because they lacked food as well, regardless of age, and also lacked education: so everyone left for Santarém and went to live on the periphery of the city, leaving behind their culture and their place in the world. Until one day they came back, and they came back because it was worth going back, and then the families stopped leaving. There is no chance there: everything happened due to the organization of the quilombola struggle, initiated by Bena himself, who one day at a seminar in the capital Belém discovered himself to be quilombola: he heard about studies regarding the territory of Tiningu and its history, which proved to be an area of slave remnants there. Bena brought this information to the community and was surprised: many of his black neighbors refused to be called quilombolas, reproducing a discourse of prejudice against this population. At the first meeting convened to discuss the issue, only 17 families appeared – Bena’s brother, his parents and his uncles included. Very few. But time passed, the struggle continued, and the quilombola association managed, pressuring the Santarém City Hall, to get funding for a health center and a new school, now with elementary school – before, there was only one nursery school in the region. As soon as today in Tiningu, 90 families call themselves quilombolas and proudly await the title of their land, a measure that will bring security to conflicts with local farmers. Conflicts with local farmers: cut in access to water and murderOne of them, a neighbor on a higher land, claiming to own the pond between his farm and the quilombo, cut off access to water for the entire community. Even the health center was short of supplies and had to stop attending. The case went to Court. In the name of the memory of his people, Bena takes good care of the local cemetery – the area was in dispute with another farmer, who had to give in due to the historical importance of the site. The land of this farm is now cut out by a square where gravestones with bodies and stories of struggle are buried. It is there that he recalls another recent case: the keeper of another farm, in a conflict of little explanation, murdered one of the quilombolas, supposedly after a fight. He is a fugitive to this today. In the name of memory, Bena outlines a plan: to transform the old children’s school into a museum of quilombola history in the region. Uncle Babá’s oral record will gain historical preservation and no one will ever again forget that the struggle changes life. Return to the central page “What really happens in the Amazon Forest“ Also read parts 2, 3 and 4 of the introduction:– Who

Curuaúna: on one side, soy. And on the other? Also soy

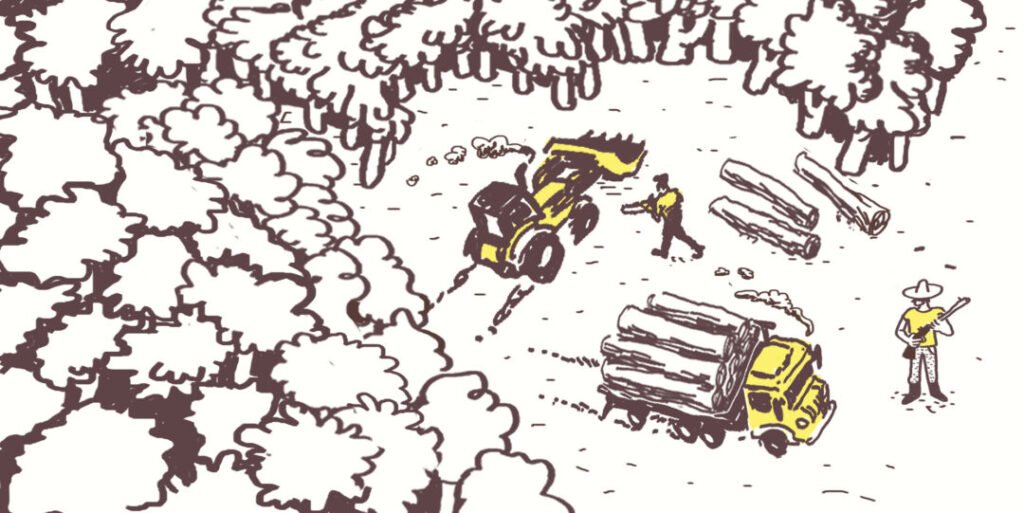

Above Tiningu and Bom Jardim communities, one reaches the Curuaúna region. Poison oozes from the vast soy fields towards the quilombos and the waters of the Maicá River. Driving and walking around the region, Francinaldo Miranda, member of the Union of Rural Workers and Family Farmers of Santarém (STTR-STM), shows the skillful architecture of soybean farmers, or perhaps the skill in design of environments – This is the “puxadinho”, which comes down to a small advance – no more than two or three meters – from the soybean field towards the standing forest; then the forest is burned little by little year by year as if nothing is happening. Slowly soy takes up all the available space – as if it needed to grow more: today, it can be said that in the middle of the soy field there’s a forest (there’s a forest in the middle of the soybean field) – And they build this “wall” so that the view of the road is blocked. Nobody sees anything and the forest seems to be alright. The wall in question is a thin strip of trees that does fulfill its role: it is only by going around it that one can contemplate the immensity of soy – soy to be lost sight of, on one side, on the other side, ahead and behind. However, from the road, it is as if the trees were still standing tall. This is one of the stories of “What really happens in the Amazon Forest”. Browse content: INTRODUCTIONPart 1 (central page): What really happens in the Amazon ForestPart 2: Who is favored by Bolsonaro’s responses to the fires?Part 3: The “win-win” of companies with the financialization of naturePart 4: But after all, who is behind these crimes? STORIES1) The siege explained on a map2) A port stuck in the “mouth” of the river3) Before the port arrives (if it does), the impacts already did4) Health center and quilombola school: the struggle changes life5) [you are here] Curuaúna: on one side, soy. On the other? Soy also6) A face printed on a T-shirt The impacts on the forest and on local communities are tremendous: soy represents land grabbing, fires, deforestation, vast use of pesticides, in addition to needing an entire infrastructure for its transport and export, which also impacts the peoples of the region. But some cases reach the absurd: as the situation of a small school in the community of Boa Sorte (and the name seems a sadistic irony of life: Boa Sorte means “good luck” in English). The distance between the classroom window and the soybean field does not reach two meters, and the most serious: the use of pesticides does not respect school hours and is repeated several times a year. Contamination of children is direct and repeated. The Curuaúna region is so impacted by the use of pesticides (the main one is glyphosate – Monsanto’s Round-Up) that blood has been collected from residents and studies are being carried out to measure the size of the damage to people’s health. The results of this research have not yet been released. Other studies, however, are available: this is the case of the dissertation by Nayara Luiz Pires, from the University of Brasília, who in 2015 researched the expansion of the agricultural frontier in the Amazon and the contamination by glyphosate in the Santarém region. In it, the researcher states “a probable risk of human exposure to pesticides, mainly through the respiratory tract“. Soy “ghost-towns”Many families do not wait to find out how harmful pesticides are and how fast they are killing them. Thus, communities are gradually being abandoned, disappearing from the map, ceasing to exist – There was a football field here, – There were a lot of houses there, – Here was a school, shows Francinaldo as you go along the road that cuts through the fields of soy. Even the traditional football matches between neighboring communities are in danger of not happening anymore, simply because ghost towns do not have football teams: no one else will be able to challenge the feared São Jorge, the team to be beaten in the region. Francinaldo, a native of the Curuaúna area, was a goalkeeper and tells when – The striker was just a few meters from me and was one of those who kicked hard, my friend even, but he kicked with anger, and the ball was so fast, but so fast, that it tore Francinaldo’s belly, what he only discovered later, after the match, as he dragged himself with the bike home so as not to accuse the pain in front of the opponent. It even required surgery and it took years to fully recover. Most importantly, however, he succeeded: he defended the kick. Thay’s what the advance of agribusinness and monocultives mean: in addition to death and contamination and land grabbing, the end of culture and local life. Return to the central page “What really happens in the Amazon Forest” Also read parts 2, 3 and 4 of the introduction:– Who is favored with Bolsonaro’s responses to the fires?– The “win-win” of companies with the financialization of nature– But after all, who is behind these crimes? And the stories:– The siege explained on a map– A port stuck in the “mouth” of the river– Before the port arrives (if it does), the impacts already did– Health center and quilombola school: the struggle changes life– [you are here] Curuaúna: on one side, soy. On the other? Soy also– A face printed on a T-shirt

A face printed on a T-shirt

The eyes pointed straight at the print on the shirt and there they got lost, taking a long time to return – Is it Maria do Espírito Santo? It’s her, isn’t it?, and the answer was “yes”. Who asked about the image that appeared on the T-shirt of one of those present at the celebration of the 46th anniversary of the Union of Rural Workers and Family Farmers of Santarém (STTR-STM) was Maria Ivete Bastos dos Santos, 52 years old – seven of them dedicated to the presidency of the organization, between 2002 and 2008. Chico Mendes, Marielle Franco, Dorothy Stang, Berta Cáceres, among others, were also looking at her from the white fabric of the shirt, with serious look. The print was a tribute to the defenders of territories murdered in Brazil and in Latin America in recent decades, as well as a protest for the lack of solutions to these crimes. The voice trembled for a second before returning to the usual firmness: seeing the face of her friend Maria do Espírito Santo caught the other Maria, Ivete, unprepared – I wasn’t expecting to see her today, and from then on she remembered: and sometimes memories are a heavy hurtful burden. This is one of the stories in the story “What really happens in the Amazon Forest”. Browse content: INTRODUCTIONPart 1 (central page): What really happens in the Amazon ForestPart 2: Who is favored by Bolsonaro’s responses to the fires?Part 3: The “win-win” of companies with the financialization of naturePart 4: After all, who is behind these crimes? STORIES1) The siege explained on a map2) A port stuck in the “mouth” of the river3) Before the port arrives (if it does), the impacts already did4) Health center and quilombola school: the struggle changes life5) Curuaúna: on one side, soy. On the other? Soy also6) [you are here] A face printed on a T-shirt7) The motorcycle night In the state of Pará, one of the most dangerous for those who defend the rights of peoples, the two Marias fought side by side. Maria Ivete, president of STTR-STM, in addition to other positions she has held in the union over the years; and Maria do Espírito Santo, who with her husband Zé Cláudio worked and lived at Praia Alta Pirandeira Agroextractive Settlement, in Nova Ipixuna, near Marabá. Facing illegal loggers and ruralists in the region, the couple were constantly threatened. Zé Cláudio already knew about his destiny, that he was going to die, and he told the world about it – but the effort didn’t make a difference: both were murdered by gunmen in an ambush inside the reserve where they worked for 24 years. Zé Cláudio speaks at a TEDx. Subtitles in English available. The cowardly crime occurred in 2011. Since then it has been nine years of mourning for Maria Ivete – I told her not to take the bike that day, although she knows this is a mere detail – It is not a threat what we suffer: it is a sentence, and it is almost as if it were only a matter of time before the ordered death finds the condemned life it’s supposed to take. In the meantime, the threat is a kind of anticipation of death to life, an absurd inversion in the natural order of things. The sentence that hangs over so many heads prevents life from being lived to its fullest – although, strictly speaking, one is still alive, and the heart still beats and the lung still breathes and the brain still remembers, at hard costs. As that case took on large proportions and had international repercussions, the two gunmen who murdered Maria do Espírito Santo and Zé Cláudio were condemned by the courts. The person who ordered the crime, after being acquitted in 2013, went to a new trial three years later and was found guilty. The penalty: 60 years in prison. However, only one of the killers is in jail. José Rodrigues Moreira (the one who gave the order) and his brother, Lindonjohnson Silva Rocha (executor), have been at large since November 2015 – I can’t speak of justice, so I speak of injustice, and that’s the reference, after all: injustice is what is known and experienced, leaving its opposite – justice – somewhere on the horizon, distant and unreal. Protection for defenders of peoples’ rights is still insufficientIn Pará alone – and still in 2017 – 90 people were on the list to join the Program for Protection of Human Rights Defenders (PPDDH). The state is the third with the highest number of people within the program. For Maria Ivete, it has been around ten years living with escorts, restrictions on hours and movements: today, she is accompanied by the State Program for Protection of Human Rights Defenders in Pará, which accompanies 77 people there. But it is not security what she feels, on the contrary: to live with protection is to remember the threat of death daily – I don’t go to parties, in the places we go we don’t go out to a bar, nothing. The PPDDH – although an important advancement (it came up as a reaction to the murder of the missionary Dorothy Stang, also in Pará in 2005) – is still quite precarious. It needs articulation in the states; however, it has programs implemented through agreements in only six – Bahia, Rio de Janeiro, Pernambuco, Ceará, Minas Gerais and Maranhão. In Pará, operationalization takes place through a central in the capital Brasília. The main question is yet another: the program proves to be useful only when the situation is already extreme – in cases of persecution and attacks. It is thought that surveillance by the State can at a minimum constrain the work of the murderers. However, ending the attacks on defenders of peoples’ rights requires a structural response: land redistribuition benefiting small farmers and landless workers; as well as the demarcation of indigenous lands and traditional communities. In its recommendations to

The motorcycle night

Vruuuum vruuum vruuuuuum and the noise woke José Marques da Costa, a rural worker from Alenquer, a small municipality in the state of Pará with just over 50 thousand inhabitants. Of the 53 years that José carries on his shoulders, most of it was filled with restless nights: there’s no easy sleep in the corners of Brazil for those who dare to defend the rights of small farmers and rural workers – exactly what José does, and when he heard the fourth vruuum he stood up, alert. A few months earlier, new messages had reached him (always indirectly, cowardly warning, “send word”) – We will kill about five of you people, they will not even know and – Justice is slow, in the bullet we can solve it faster. If before José slept with one eye open he started to open them both on nights of little or no rest. And if television seemed like a good medicine to make him sleep what actually happened was the opposite: the dragging voice of the current president of the Brazilian Republic, Jair Bolsonaro, echoed from the device and only aggravated José’s insomnia by saying things like – Who should have been arrested were the MST people (Landless Workers Movement), those vagabonds. The policemen reacted so as not to die, and – Let’s shoot who is from the Labour Party in the state of Acre, huh! Hate speech that encourages and materializes violence against rural workers in the Amazon Region and in Brazil: against him, José. The first Bolsonaro’s sentence refers to the Carajás Massacre, when the police in Pará murdered 19 landless workers in cold blood; the second was said during the 2018 presidential campaign. Vruuuum vruum followed the noise, and José Marques risked a glance out on the street. Motorcycles. Many motorcycles – One, two, three, half a dozen, nine, ten, he was counting, but the task was hampered by the constant circular movement of the vehicles, accelerating and decelerating in front of the house. Twenty, it must have been something near that, and soon José started to focus not on the bikes but on who rode them: that was certainly a matter of greater importance. That was when he saw neighbors, friends, colleagues, and the fear that had settled in his chest gave way to a little curiosity – What are you all doing here at this hour? and then commotion took place: the circus set up there was not an ambush. On the contrary, it was an escort to protect him exactly from attack and possible murder. Since the end of the day the rumor had run through the small town that gunmen – All very treacherous, they’ll drink a coffee at your house before killing you, these treacherous gunmen were lurking on the road, ready to attack José Marques when he left home. Death ordered by the big farmers in the region. The twenty or so motorcycles would serve – and did serve – as a shield to take José Marques to a safe place. That was how he got on his motorcycle, in the middle of the night of little Alenquer, took off and lived to fight another day among and for his people. Land grabbing: overlapped CAR and “Four Years of Storm”What led gunmen to pursue José Marques is related to the long-named position he carries: president of the Community Association of Residents and Small Farmers of the Limão Grande Community, located in Alenquer. There, 86 families lived and worked in an area of around ten thousand hectares – until, in 2016, what José called “Four Years of Storm” began. First, there was the requisition – by farmers – of three thousand hectares of the area where the families lived. In consultation with Incra (National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform, in English), with the support of the Union of Rural Workers and Family Farmers of Alenquer (STTR-ALQ), it was shown that the request was fair: the families accepted to leave that area, redistributing themselves in the seven thousand remaining hectares. In the meantime, the land was georeferenced, a necessary step for the community to register in CAR (Rural Environmental Registry, in English). Work done, they returned to Incra and then came the surprise: fifteen days earlier, several people had registered those areas as their own. Suddenly, the land where families have lived since 2007 had “owners” – and they were others. There was never any inspection by Incra to verify if those who registered in CAR actually occupied the self-declared land; if there were one, it would be simple to see who actually occupied the area – They didn’t even know where it is, however José does and this seems to be of no use. The registration, based on the information provided by the applicant, has no deadline for verification by the competent public agency: some states claim that the analysis of the registrations would take from 25 to 100 years. However, contrary to the popular imaginary of slowness in justice, long before the due inspection could take place, the repossession of the site was decreed – which happened with a strong police apparatus. In short: 86 families were thrown out on the street. Everything they had was left behind – clothes, crops, houses – and what was left behind was set on fire and tored down. The videos above were recorded by local families. The first one shows the fire consuming a building next to a plantation; the second shows the remaining ruins; the last video denounces the destruction of the only access bridge to the area, a service performed by the henchmen of the land grabbers. In the photo, also made available by residents of Limão Grande, heavily armed private security guards prohibit the movement of rural workers in the disputed territory. Nowadays private security guards roam the territory. Rifles speak loudly and anyone who ventures to look for something that may have left behind (and sometimes despair is prone to

If well organized, everyone fights

It was a long journey: from Santarém to Alenquer it takes two hours by ferry and another three or four hours by car, part of it off-road. So Totó – a much silent man – and Mara – a talkative woman – took the opportunity to tell some of the stories they have witnessed in the past. He as the former president and today vice-president of the Union of Rural Workers and Family Farmers of Alenquer (STTR-ALQ); she as the current president of the organization. In all stories was highlighted the importance of the workers union for the conquest and guarantee of rights, from technical assistance services to the safety of rural workers. This is the last part in the story “What really happens in the Amazon Forest”. Browse already published content: INTRODUCTIONPart 1 (central page): What really happens in the Amazon ForestPart 2: Who is favored by Bolsonaro’s responses to the fires?Part 3: The “win-win” of companies with the financialization of naturePart 4: But after all, who is behind these crimes? STORIES1) The siege explained on a map2) A port stuck in the “mouth” of the river3) Before the port arrives (if it does), the impacts already did4) Health center and quilombola school: the struggle changes life5) Curuaúna: on one side, soy. On the other? Soy also6) A face printed on a T-shirt7) The motorcycle night8) [you are here] If well organized, everyone fights Alenquer is a small city, just over 50 thousand inhabitants. And it is unstable: mayors don’t usually complete their mandates – it has become a tradition. That same day, while Totó and Mara would tell stories, the president of the City Council took over as mayor in yet another plot-twist of local politics. Years ago in the middle of the unstability, outraged by the absence of public investment in the region… A pause: Totó, whose real name is João Gomes da Costa and is 47 years old, looks in the rearview mirror and sees a big white truck pass by. When already in front of the car, it starts to drive really slowly – and then it accelerates sharply and disappears on the horizon. Mara, short for Aldemara Ferreira de Jesus, 37 years old, takes a note: the car license plate is from Santarém. …outraged by the absence of public investment in the region; and also with the delayed payment of teachers and health professionals; and with the poor condition of the roads; to make it short – it was a complete package of indignations: that’s when the people from Alenquer decided to block the main road to the city. That happened after the mayor had refused on several occasions to sit down and talk – he even expelled Totó and Mara from meetings – and took his disinterest to the point that the road had to be blocked by people. A crowd of workers from different areas gathered on the road: there were rural workers, organized by the union, and also teachers and health workers, and street sweepers, and people from the church – everybody was there – and then the mayor and his secretaries and judges appeared quickly and a meeting was arranged at the City Council later that day. It was agreed that only 50 representatives of civil society could enter and present their demands. Ok, not a problem. The police “tactic group” arrived first at the City Council – an exaggeration and it was a great embarrassment when even the nuns and the priests were searched to enter the meeting room. Then people spoke – and immediately afterwards without any response or a slight indication that he paid attention the mayor left. Mara and Totó had no choice but to go out to the front of the City Council to tell what had happened in the building. To their surprise there was a mass of people waiting for the result of the conversation – over a thousand people who obviously were not happy with the news: it started raining eggs and tomatoes on police shields and helmets. From a corner, a desperate cry was heard – Totó, control the people, to which he, Totó, thought – How? but he replied – If there’s anyone to blame here it’s you, you promised to talk and didn’t talk, and the eggs and tomatoes kept flying and exploding in the building walls and on shields, the crowd getting more and more inflamed – and then the mayor and the secretaries reappeared and this time everyone was very willing to listen. Finally agreements were made and commitments signed. Mara laughs now – If the workers understood the strength they have when united… They would never be taken for granted. Persecution and threats– Taking the poor people side has a consequence, says Totó, and he knows that quite well. He worries about the threats he receives, he worries about him and his daughter and son, and it took him a few seconds to say – Yes, I’m afraid, we lose our freedom. I think about mine and my children’s schedules, I keep an eye out for anything that is different, everyday I think about how it will be when I get home, if there is an ambush or not. But he sleeps peacefully, he guarantees – We have a clear conscience, although always attentive and concerned. Concern that Mara shares, along with embarrassments such as when her daughter asks – Mom, what are they talking about you on Facebook?, and there are things that are complicated to explain to children, it’s complex and it’s exhausting and it’s serious: it is serious because sometimes the threats come from the State itself, represented in the men in uniform who should give protection to everyone. Totó reports receiving calls from police officers saying – We are with that farmer, in the intention of intimidating him. The message is very clear and Mara and Totó feels unprotected – Where you would find some protection, you have none, he complains